Like most blogs, this publishes in reverse chronological order. Want to start reading at the beginning of the trip? Click here.

The New New China

Shanghai, Oct. 25-27

This is the final post in my Internet travel diary. I have been back in the States for more than two weeks, and any pretense that this is a daily account of a trip to China has been exposed as fiction. When I began this project, I thought it might take an hour or two each day along the way—a small price to pay for a subsidized trip to China. But the overwhelming input of information and images that any sort of travel provides made it impossible to keep up in a contemporaneous manner.

Readers who have followed all of these thousands of words and hundreds of pictures deserve a People’s Hero medal. I could have bought some, just off Tianamen Square, two for a dollar. I should have gotten you one.

The December 2007 Swarthmore College Bulletin will carry an article on our China adventure. In a few magazine pages, it won’t begin to capture the breadth of our group’s experiences during the past few weeks. I asked travelers to write down their “elevator speeches” about the trip—those one-minute encounters that occur when a friend or colleague asks, “How was China?”—and I’ll include some of those.

Prefer to start reading at the beginning of the blog? Click here.

The last leg of our trip brought us from Xi’an to Shanghai on a very crowded aircraft. Our knees-knocking flight arrived just after dark. The airport looked much like Xi’an’s, much like Chongqing’s—only much, much larger. As in each new city, we were met at the baggage claim by a cheerful guide. And, like ducklings in the famous children’s book about the Boston Common, we followed his flag through the airport. But thankfully, we were not headed for another bus. This time, we were to ride a very fast train—the Shanghai Mag-Lev, which would whisk us into the city (well, almost all the way) in less than 10 minutes. Top speed: 300 km/hour—just under 200 mph. Whoosh!

A Maglev poster.

The train—which has no engineer on board.

Speedo sign. We reached 300 km/h in less than two minutes. Higher speeds are reached in the daytime. Not sure what the difference is at night.

China is on the move. Fast. We saw the biggest dam in the world. We rode the fastest train in the world. If we come back to Shanghai in a few months, we could ascend the tallest building in the world. While we were in country, the Chinese put a satellite in orbit around the Moon. If there is any take-home message, it’s that, although the 20th century might have been the “American Century,” the 21st will belong to China.

This is not a defeatist observation. It is, however, a call to get over it, get used to it, and get ready for it. Those who believe that American leadership of the world’s economy, currency, geopolitics, military power, and culture are permanent conditions—or some sort of natural right—are fooling themselves. What we have seen is but a glimpse of the enormous power and creativity that will surely dominate the world during the next 100 years.

Our China experience was carefully choreographed—not so much by the Chinese themselves (though our guides were perfectly programmed) but by the larger sweep of culture and history—and by the desires of tourists like us—the perceptions of culture and history that shape everyone’s view of what’s important to see in China.

Beautiful old bronzes and ceramics in the art museum in Shanghai are the foundation of a culture that is 4,000 years old. Next door, a city planning exhibit shows the scope of the city, which locals claim is the world’s largest.

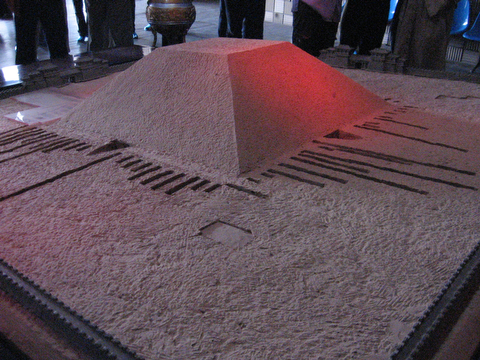

Part of the planning exhibit was a huge scale model of the city. All I could think of was where to put the model trains. My old Lionel 027-gauge tracks would look pretty silly in this world.

Shanghai at night—along Nanjing Road, the main shopping street.

Dick and I took a long walk in the late afternoon. The street holds endless opportunities. We took the subway under the river to Pujong, opposite the old colonial district, where we emerged in a sea of high-rise towers.

The Bund—along the river where Western-style buildings give a hint of Paris or London.

Looking across the river to Pujong.

Objects of extraordinary beauty in the museum included this sculpture, which held my gaze for a long time.

This extraordinary Buddha, made of jade, about 1.5 meters tall, is not in a museum but rather in a working Buddhist temple, next door to a restaurant where we had a delicious vegetarian lunch. It glows as if alive. I was mesmerized and did not want to leave the room. (Not my photo.)

Some Final Thoughts

Being in China has presented a complicated dance of expectation and reality. Flying over the pole a couple weeks ago, I had no idea what I would find. All I had was an open-minded excitement—a nervous anticipation and desire to know. Most of us arrived in Beijing with no direct experience of this vast country (only two or three had ever been here—except for Haili Kong, who was born and raised in China), but it wasn’t an entirely blank slate, just a blurry one. There is no such thing as a blank slate. Each of us brought our own ideas of Chinese culture and history, from what the food would be like to how the people act to what we would encounter on the streets.

Few of these preconceptions turned out to be accurate. This is the whole reason to travel in this world: to replace preconceptions with reality—or at least as much reality as can be obtained on a superficial tour such as this. Which is to say that not everything we saw was “real.”

Our tour was scripted by many authors, not the least of which were our own preconceptions of what we ought to see in China. We followed a well-trod tourist track, seeing many of the same things that almost every visitor to China gets to see. Yet, had the Alumni College itinerary not promised those sights, few would have desired to spend thousands of dollars on this trip. Or any trip.

The genteel and urbane Howard Smith, our tour operator, is a 30-year China veteran specializing in custom trips for educational groups such as ours. With few exceptions, his choices of destinations, guides, accommodations, transport, and restaurants were masterful and delightful. But—and this is a criticism of tourism itself, not Howard—they merely reinforced a familiar story. With his long experience of contemporary China and many friends here, Howard could surely have told us a somewhat different story. But could he design a two-week tour to illustrate it? Doubtful. Could you impart the story of your last 30 years (not to mention your entire country’s) in a 14-day travel experience for 40 people?

I love travel, and in each place I visit, I hear a series of little stories that build like chapters in a book. But, I wonder, are they truth or fiction? Can any person know China’s whole story? Or America’s? It’s like meeting a friendly stranger on the street; you can talk for an hour (about as long as it seems we were in any one place in China), yet nothing is certain when you are done. You cannot be sure.

So it’s like any other place: You know what you think you know. Over a lifetime, you watch, read, listen, think, see, absorb, accept, believe, reject, and ultimately form a story—a few lines to repeat when someone asks you about your experience. How was your vacation? How was Christmas? How was China? are the questions you must answer when you see family, friends, and co-workers. How indeed?

Better to ask, “How are you after your two weeks in China? How has it changed you and your perception of the world?” It may seem like an easier question to answer, but it’s not. Travel enhances self-awareness—especially in a culture so different from ours as that of China. What you bring home is not new knowledge about the place you have seen but about the mind that has seen it.

I took 1,600 pictures on this trip. Some of them are quite beautiful as photographs; others document what we saw along the way; but none of them captures the changes that occur in the traveler. Travel is about change—in latitude, longitude, and attitude. After two short weeks in China, I have a new and different understanding of that country—yet one that may or may not correspond to reality there. The only truly new and different understanding that I can trust is the one I have brought home about myself.

How was China? Better to ask me, “How’s life?”

Thanks for reading.