Want to start reading at the beginning of the trip? Click here.

Xi’an to Shanghai

Oct. 25

The next day, just before leaving for the airport, it was time for another undergound experience: the mausoleum of LiuQi (188-141 BCE), the fourth emperor of the Western Han dynasty and his empress, Wang. Construction of two large funeral mounds began in 153 BCE near present-day Yangling.

One of the Han Dynasty burial mounds near Yangling. (Not my picture—the sky was never this clear while we were there.)

What it really looks like in late October.

Excavations around the edges of the mounds have revealed another huge underground collection of terra cotta figures—ranks upon ranks of them, representing not just warriors but ordinary men and women (complete with their genitals and other bodily orifices). They were painted and equipped with movable wooden arms, which have rotted away. They were even clothed for their journey—probably with items labeled “Made in China!”

Work at this site is even more recent than those at Bingmayong, beginning in the early 1990s. Another magnificent museum has been built around these excavations—which represent a fraction of the size of the entire complex. Underground imaging has revealed that the mound itself is like a palace inside—the perfect combination of palace and tomb, and therefore the perfect tourist site—but it is not clear whether archeologists will ever excavate it, because to do so might destroy it.

According to one Chinese Web site,

From a site which accounts for only one thirteenth of the total area of the sacrificial burial pits, about 600 color-painted pottery figurines and 4,000 pieces of various cultural relics were unearthed. The figurines included warriors escorting the imperial chariot, attendants watching over boxes and cases, cattle drovers and clerks. There were also animal models produced in different styles.

Here are a few pictures. It was, as you will see, very dark down there.

We were issued little blue booties before we entered the museum, which takes you underground by a series of ramps to stand on glass floors above the excavated burial chambers.

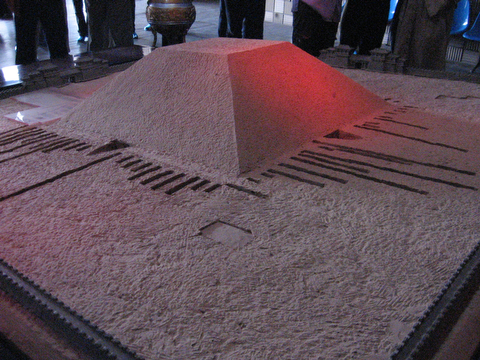

A model shows the sacrificial burial pits radiating out from the four sides of the mound.

Ashes to ashes, all fall down.

The wooden arms of the figures, which are about 60 cm tall, have rotted away over the centuries.

A chariot wheel—about a meter in diameter.

Livestock. The piggies are really cute.

Back outside, pots of chrysanthemums—just like fall at home.

The tombs near Xi’an are one of the top attractions in China, and I’m glad we got to see them. But I suspect that one reason we like to tour the world’s tombs and palaces is that, after all this packing for the afterlife, the aancient kings left it all behind. They are gone and their stuff remains. There’s a certain satisfaction in knowledge that they couldn’t take it with them after all. And, of course, there’s a lesson there for the rest of us: Pack light. A robe and a rice bowl may be all you need in this life—and you won’t even be able to take those simple things to the next.

We headed for the airport, where lunch was served in a large dining room set aside for tour groups. The modern air terminal will be taxed to its limits next year, during the Olympic, because every potential visitor to China has seen pictures or heard of the terra cotta army. They will all flock here, and the locals will house and feed and transport them, then cram them back on airplanes to the next stop. Our next (and last) stop: Shanghai. For those about to go to China, what you really should pack is a smaller set of legs, because there isn’t room for your current pair on Chinese airplanes. Be my witness:

This was before the person in front of me reclined his seat.